WW1 Armistice Exhibition - Recruitment

Recruitment, Enlistment and Conscription

Enlistment was a free choice until Jan 1916 when conscription was introduced to sustain troop numbers.

Although a staggering total of 2,466,719 men had volunteered to date, conscription had become inevitable. A register taken in Aug 1915 revealed that there were over two million single men of military age still not in the army.

Although a staggering total of 2,466,719 men had volunteered to date, conscription had become inevitable. A register taken in Aug 1915 revealed that there were over two million single men of military age still not in the army.

Recruitment

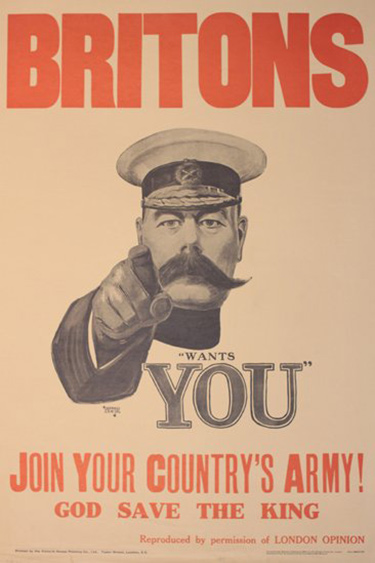

Poster campaigns were crucial and worked alongside film and press advertising, pamphlets, house-to-house canvassing and promotions, and meetings held by MPs and celebrities. Even songs encouraged recruitment.

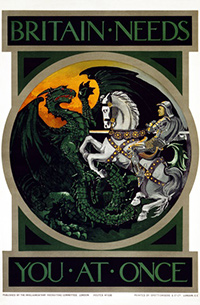

A positive representation of what the ‘new armies’ were fighting for was a priority for the British Government. Poster illustrators needed to emphasise British values of family and country. Positive depictions, so different to the realities of warfare, were essential to show that recruits were engaging in military life and enjoying the experience.

By the spring of 1915 men were enlisting at an average of 100,000 per month. To maintain numbers the upper age limit had been raised to 40 years. In spite of heavy recruitment, the numbers were lessening and enthusiasm was drying up.

Posters urged men to cultivate a sense of duty owed to their country; every man was equal in this plight to defend their home.

Posters urged men to cultivate a sense of duty owed to their country; every man was equal in this plight to defend their home.

This poster evoked the golden medieval age, with St George spearing the defeated dragon with his lance.

It suggested that military service was heroic.

E motional blackmail was used.

motional blackmail was used.

The bombardment of Scarborough by the guns of German Naval Cruisers in December left devastation in the small north-east seaside town. It woke local people up to the harsh reality of war and possible invasion.

The Scarborough attack was exploited to evoke anger.

Naming and shaming

Families would boast of fathers, husbands and sons enlisting, it was a “feather in the cap”. Some men needed a push. To persuade them the government sanctioned local authorities to withhold benefit relief payments until they did join up.

The alternative “feather” was white in colour. To be given a white feather marked a man out as a shirker and a coward. Recollections from recruited men tell of the fear of being handed a white feather in the street.

Images of children were key in shaming non-enlisted fathers.

- copyright © 2024

- Site by lancefrench.com